Showing all posts about psychology

The people we spend time with changes throughout our life

8 August 2022

A breakdown of the time we spend with the people in our lives: parents, siblings, friends, partners, colleagues… and ourselves, put together by Our World in Data. The findings are based on surveys conducted between 2009 and 2019 in the United States.

- As you age you tend to spend more time alone. This does not necessarily mean you’d be lonely though

- Once you leave home the time spent with parents and siblings plummets

- Once settled in a career, time spent with friends also decreases

- In fact the only person you spend more time with, excluding children if you have any, is your partner

RELATED CONTENT

data, lifestyle, psychology, science

Absurd instances of the trolley problem by Neal Agarwal

8 July 2022

Most people have heard of the trolley problem. In short, you’re standing beside a rail line, near a railroad switch. A train is coming along the track, but there are five people tied to the track, in its path. You have the option to pull the switch lever, sending the train along a side line.

But another person is tied and bound to the side line. What should you do? Stand there, do nothing, and allow the train run over the five people? Or send the locomotive down the side line, where one person will be killed? Presumably there is not time to free any of the people, so you are left with the difficult choice. Do five people perish, or one?

This format of the trolley problem was created by Philippa Foot, a British philosopher, in 1967, while Judith Thomson, a philosopher at MIT, devised the quandary’s name. American creative coder and developer Neal Agarwal, meanwhile, has thought of a few more, absurd, trolley problem instances.

RELATED CONTENT

Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi: an introvert on steroids?

27 May 2022

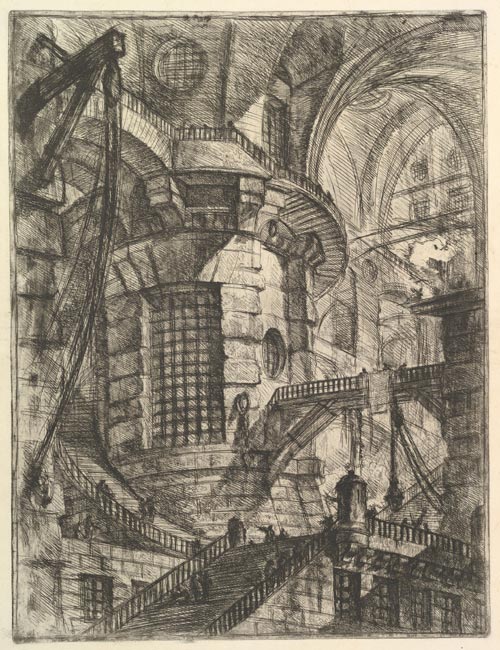

Detail from Imaginary Prisons, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Warning, spoilers follow. Return to this article once you’ve finished reading the book.

Imagine you live in a sprawling multi-storied house. The lower levels are flooded by an ocean, while the upper floors are shrouded in mist and clouds. The seemingly endless labyrinth like hallways are adorned with classical style marble statues, and for whatever reason, sea birds have taken to nesting among some of these figures. But it’s not really a house you’re in, it’s more like a complex with the dimensions of a city, and one none too small at that.

This is the world, Piranesi, the titular character in the second novel of British author Susanna Clarke (published by Bloomsbury Publishing, August 2021), finds himself in. Piranesi knows little about how the house came to be, or when he arrived there, although he has vague recollections of living elsewhere before. Come to that, Piranesi knows hardly anything about himself. He’s perhaps aged in his mid-thirties, and if pressed, couldn’t even be sure his name was Piranesi.

Despite these peculiar circumstances, Piranesi otherwise seems content, and goes about his day to day life as if nothing were amiss. But how would you feel were it you in Piranesi’s place? Wouldn’t you wonder how you ended up in this predicament, and whether there was a way leave, and return to the real world? Wouldn’t you miss family and friends, and wonder if they felt the same way? Wouldn’t you crave the company of others at least some of the time?

But Piranesi doesn’t appear to be the least bit perturbed. Why though? Does he have some sort of problem? Does he loathe all people, and is thankful for the sanctuary the house offers, a place devoid of humans? Or is he perhaps an introvert, who’s found his happy place? Yet Piranesi isn’t completely alone in the house. Once or twice a week, he goes to a certain area of the complex, where he briefly meets a middle-aged man, whom Piranesi refers to as The Other.

If Piranesi knows little about himself, he knows even less about The Other. He has no idea who this gentleman really is — although he believes him to be some sort of academic — nor does he know where The Other resides in the house. The Other meanwhile frequently questions Piranesi, and even sets him tasks, some relatively arduous. One such request required Piranesi to walk to a distant point in the house, on a journey lasting two days return.

To make a comparison, and better understand the scale of the house, I looked up the walking time and distance from Sydney’s CBD to the western suburb of Penrith on Google, and was advised the trek is approximately fifty-six kilometres in length, and the non-stop walk would take almost twelve hours.

Of course the question of exactly what sort of place Piranesi finds himself in came up repeatedly as I read the novel, particularly as he never encountered anyone else — at least not at first — in the sprawling complex. While plenty of Clarke’s readers (myself included) have ideas as to the nature of the house, and what it really is, I found myself wondering how Piranesi could remain oblivious to his acute isolation, and not miss the company of other people.

After all, surely not even the most extreme of introverts would continuously crave the deep solitude of the apparently empty house. But there were indications Piranesi was lonely. He regarded the sea birds nesting in the statues in some of the hallways as friends, and would often have conversations — albeit one-sided — with them. But when it becomes obvious another person is lurking, out of sight, in the house, Piranesi is keen to find out who they are.

In trying to understand Piranesi’s apparently people averse personality, I would describe him as an introvert. But no ordinary — if there is such a thing — introvert. To live alone for years in a vast complex, spending perhaps an hour at most, once a week, with one other person could not be anyone’s ideal. While it can argued something else is going on, that he is unaware of, Piranesi’s outright acceptance of his plight remains compelling. Piranesi is certainly an introvert, but he’s more, he’s an introvert on steroids.

RELATED CONTENT

fiction, introversion, novels, psychology, Susanna Clarke

The benefits of having a dual identity are real

22 April 2022

Thinking of yourself as another person, in the same sort of way Bruce Wayne thinks of himself as the Batman, may be surprisingly empowering. You don’t need to imagine you’re a superhero though, even assigning yourself a pseudonym may be sufficient.

Although the embodiment of a fictional persona may seem like a gimmick for pop stars, new research suggests there may be some real psychological benefits to the strategy. Adopting an alter ego is an extreme form of ‘self-distancing’, which involves taking a step back from our immediate feelings to allow us to view a situation more dispassionately.

“Self-distancing gives us a little bit of extra space to think rationally about the situation,” says Rachel White, assistant professor of psychology at Hamilton College in New York State. It allows us to rein in undesirable feelings like anxiety, increases our perseverance on challenging tasks, and boosts our self-control.

RELATED CONTENT

Lockdown, an introvert’s paradise, now sadly missed

28 March 2022

Almost two-thirds of readers surveyed by London based magazine The Face reported missing pandemic imposed lockdowns, with many reporting “significant improvements in day-to-day-life.”

You might be surprised to learn that an overwhelming majority of respondents reported that, yeah, actually, they did miss lockdown life – 66.9 per cent of them, to be exact. For all the sadness and boredom born out of the pandemic, many of you experienced significant improvements in day-to-day-life.

As an introvert who enjoyed lockdowns, I couldn’t go passed this thought:

“[Lockdown] was an introvert’s paradise. I miss it immensely,” says 23-year-old Sarah, who also described the most challenging thing about the pandemic was “it ending”.

RELATED CONTENT

introversion, personality, psychology

The National Pleasure Audit

4 February 2022

The National Pleasure Audit is presently open to Australians aged eighteen and over. Conducted by Dr Desirée Kozlowski, a researcher at Southern Cross University, the audit aims to find out what brings joy — by whatever means — to people. Participation is anonymous, so anything goes, though you can submit an email address if you wish to be sent the results of the audit.

RELATED CONTENT

The difference between introversion and social anxiety

17 December 2021

Kylie Maddox Pidgeon is a Sydney based psychologist, who is also an introvert. The world needs more psychologists who are introverts, because there are some psychologists who are extraverts but appear to have little real-world understanding of introverts. To put it mildly. One once told me I needed to be more outgoing, because I seemed to be too reserved. Thanks for that.

Kylie is a psychologist, academic and introvert. I met Kylie playing netball in the Blue Mountains in New South Wales and I wouldn’t have guessed she was an introvert. She loves socialising and sparks with energy during conversation, but she says if she overdoes it, she feels drained and can experience headaches.

My favourite analogy when explaining introversion is to suggest introverts have a constantly playing media device in their minds. There’s times we’re able to turn down the volume, say for the first hour or two of a social gathering, but as time passes the volume from our in-built media device begin increasing, as the ceaseless thoughts cascading through our minds begin competing for attention. At some point we need to get away, to somewhere quiet, to make sense of this almost subconscious brainstorming.

But instead of being recognised as an introvert, our sometimes reserved demeanour can be mistaken for social anxiety. Although something else entirely, there is a link between introversion and social anxiety, but as Maddox Pidgeon points out, there is a key difference. Social anxiety occurs when a person is worried about what others will think of them. That’s generally not the case for introverts. If they’ve had enough of being at a party and want to leave, they won’t be concerned at what anyone thinks.

RELATED CONTENT

introversion, personality, psychology

Once an accident, twice a coincidence, or is it just stuff happening?

27 August 2013

Chance encounters, strokes of luck, the turn of a friendly card… Are these sorts of happenings, like say bumping into someone you haven’t seen, or heard of, in a decade in a country you’re visiting for the first time, really the long shots they seem to be?

An analysis then of chance, probability, and coincidence, such that it actually is:

The simple question might be “why do such unlikely coincidences occur in our lives?” But the real question is how to define the unlikely. You know that a situation is uncommon just from experience. But even the concept of “uncommon” assumes that like events in the category are common. How do we identify the other events to which we can compare this coincidence? If you can identify other events as likely, then you can calculate the mathematical probability of this particular event as exceptional.

Originally published Tuesday 27 August 2013, with subsequent revisions, updates to lapsed URLs, etc.

RELATED CONTENT

Fade to grey: as we get older we stop dreaming in technicolour

12 July 2011

We tend to stop dreaming in colour as we age, according to a study which surveyed a group of people in 1993, and then again in 2009.

In both surveys, approximately 80% of subjects younger than 30 years of age experienced color in their dreams, but the percentage decreased with age and fell to approximately 20% by the age of 60. The frequency of dreaming in color increased from 1993 to 2009 only for respondents in their 20s, 30s, and 40s. We speculate that color TV may play a role in the generational difference observed.

Originally published Tuesday 12 July 2011.

RELATED CONTENT

Cool kids never have the time, nor much of an adult life either

18 May 2011

Children who are marginalised at school because they are considered to be geeks or nerds, tend to be more successful as adults.

This because they are far more self aware, spontaneous, and creative, than “popular” students, says Alexandra Robbins, who has written a book on the subject, The Geeks Shall Inherit the Earth.

So called popular students are more likely to act and think according to the wishes of the groups or cliques there are part of, rather than on their own, behaviours that are unhelpful in adult life.

Even if the kids in these cliques are momentarily on top of the world, Robbins says the traits they are learning could be toxic in their future lives. “When you are in the popular crowd you are more likely to be conformist, you are more likely to hide aspects of your identity in order to fit into the crowd, you are more likely to be involved in relational aggression, you are more likely to have goals of social dominance rather than forming actual true friendships,” Robbins says, pausing for a breath. “You are more likely to let other people pressure you into doing things. None of those things is admirable or useful as adults.”

Originally published Wednesday 18 May 2011, with subsequent revisions, updates to lapsed URLs, etc.

RELATED CONTENT