Showing all posts about writing

Will Writers Australia succeed where other peak bodies have not?

3 February 2023

Writers Australia is a new peak body to be established as part of the National Cultural Policy, which was released by the Australian federal government last Monday. While the exact functions of Writers Australia — which comes into being in 2025 — are yet to be fully detailed, its stated mandate is to provide direct support to the Australian literature sector.

While hopes are high the proposed new entity will improve the lot of local writers, Writers Australia is by no means the first attempt to establish an Australian peak literature body. There have been several attempts to do similar in the past, with some being anything but successful, as Adelaide, South Australia, based author Jessica Alice, writing for Meanjin, explains:

There are two years until the body will come into operation and those working in the field will remember past attempts to create a national literature body. There was Writing Australia, the unsuccessful attempt to create a peak body for writers centres that was defunct within two years, and more recently the Book Council of Australia debacle that heralded the Brandis era.

In that instance, a national body was established to represent the interests of publishers, agents and booksellers, with $6 million in funds taken from the Australia Council’s operating budget. It faced pushback from the broader literary sector culminating in an open letter signed by high profile figures like Nick Cave and JM Coetzee arguing it was a rush-job initiated without proper sector consultation and a limited terms of reference. The body was ultimately abandoned.

RELATED CONTENT

Australia, Australian literature, politics, writing

The National Cultural Policy and the role of Writers Australia

1 February 2023

Among initiatives announced this week in the Australian federal government’s National Cultural Policy, is the formation of Writers Australia, a body that will, according to the policy document, “provide direct support to the literature sector from 2025.” Writers Australia will be part of a new peak arts investment and advisory body to be called Creative Australia, which will represent an overhaul of the current Australia Council for the Arts.

While the finer details are still to be made public, it is known Writers Australia will, among other things, administer the Prime Minister’s Literary Awards, and make appointments to the (kind of) newly formed role of Australian poet laureate.

It can also be presumed Writers Australia will work to address remuneration for Australian authors, who according to recent research earn about A$18,000 per annum for their work. Australian workers need to earn at least A$25,675 per annum to be living above the poverty line. The income of local writers is a point underlined by Sophie Cunningham, Chair of the Australian Society of Authors (ASA):

“We’re thrilled to see the Government’s affirmation that artists and authors should be paid fairly for their work. This is fundamental to a fair and sustainable arts sector. As I and many other authors made clear in our submissions to Government, authors do not fall under the protection of awards or industrial agreements and, as freelancers, have to negotiate on a case by case basis to be paid fairly. We welcome the recognition of the ASA’s recommended minimum rates of pay in cultural policy.”

While supporting writers and literary organisations through funding, Writers Australia will take a proactive role in boosting incomes for writers and book illustrators, by raising their profile, and growing local and international audiences for their books. One way of achieving this could be to encourage broader promotion of Australian literary awards, in the same way the British publishing industry enthusiastically backs the Booker Prize.

In the meantime poetry can look forward to more prominence in Australia, through the creation of a poet laureate, an appointment Writers Australia will make. There has not been an Australian poet laureate since 1818, when Michael Massey Robinson, a British convict, held the role for about two years.

Poetry is a poorly appreciated form of literature in Australia, with just three and a half percent of local book readers indicating they are inclined to read works of poetry, according to recent research by Amazon Kindle.

Dropbear, a collection of poetry by Melbourne based author Evelyn Araluen, and winner of the 2022 Stella Prize, had sold in the order of fifteen thousand copies as of August 2022. In comparison, Apples Never Fall, by Sydney based novelist Liane Moriarty, was the bestselling book in Australia, with sales of just under two-hundred thousand copies, in 2021.

RELATED CONTENT

Australia, Australian literature, poetry, politics, writing

ChatGPT cannot take author credit for academic papers published by Springer Nature

28 January 2023

The United States Copyright Office (USCO) recently declared it only wants to grant copyright protection to artworks created by people, not AI technologies.

Now Springer Nature, one of the world’s largest publisher of scientific journals, says hot AI technology of the moment, ChatGPT, along with other large language models (LLM) tools, cannot be credited as the author of any academic papers they publish. The OpenAI engineered chatbot can however assist with research writing, but their use must be disclosed:

First, no LLM tool will be accepted as a credited author on a research paper. That is because any attribution of authorship carries with it accountability for the work, and AI tools cannot take such responsibility. Second, researchers using LLM tools should document this use in the methods or acknowledgements sections. If a paper does not include these sections, the introduction or another appropriate section can be used to document the use of the LLM.

RELATED CONTENT

artificial intelligence, science, technology, trends, writing

Adam Vitcavage: the first book you write may not be published

23 January 2023

Adam Vitcavage, whose podcast Debutiful explores the work of debut authors, offers a blunt observation to aspiring writers, in a recent interview with Los Angeles based novelist Ruth Madievsky:

I think aspiring writers need to realize that your dream first book might not be what you actually publish. So many writers have said they had to shelve books they were working on for years for one reason or another. Or that they had to take what was working and reshape it altogether.

The dream book may be a story the writer likes, but no one else, unfortunately.

RELATED CONTENT

Novel serialisation, good for readers, good for writers

13 January 2023

Publishing novels by serialisation, or regular instalment, used to be a widespread practice. At one time it was the only way to read the latest works of authors such as Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell, Jules Verne, Leo Tolstoy, H. G. Wells, and Arthur Conan Doyle. Usually authors would later publish their serialised work as a complete edition, or whole book.

But book serialisation is a model some writers are again embracing. As an experiment, American journalist and author Bill McKibben published his latest book, The Other Cheek, on email newsletter platform Substack. Long story, short, the idea seemed to go down well with readers, says McKibben, writing for Literary Hub:

Still, despite all that, readers seemed to enjoy it, and for just the reasons I had hoped: the story lingered in people’s minds from one Friday to the next, and they wondered what turn it would take. As it spun out across the span of a year I got letters (well, emails) from people regularly suggesting possible plot twists or bemoaning the demise of favorite characters. I didn’t consciously adjust the story to fit their requests (and I’d written much of it in advance) but I did take note of what people were responding to.

Reader interaction and feedback during the publishing of a book, instead of as a review, or reaction, to a whole work, now there’s something.

RELATED CONTENT

Bill McKibben, books, publishing, writing

Clive Thompson: how blogging changes the way you think

5 January 2023

American journalist, author, and blogger, Clive Thompson, writing about the benefits of blogging. The audience effect is one of the positives, and will go a long way to sharpening your writing:

But blogging has another benefit, which is that it triggers the “audience effect”. The audience effect is precisely what it sounds like: When we’re working on something that will soon go before an audience, we work far harder than if we’re doing work that’s for our eyes only. For decades, psychologists have documented the audience effect in studies: If you have experimental subjects write out an explanation for other people, for example, it’ll be far longer and clearer and more comprehensive than if you ask them to write it merely for themselves.

RELATED CONTENT

Monique Judge: bring back personal blogging in 2023

5 January 2023

Monique Judge, writing for The Verge:

Buy that domain name. Carve your space out on the web. Tell your stories, build your community, and talk to your people. It doesn’t have to be big. It doesn’t have to be fancy. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. It doesn’t need to duplicate any space that already exists on the web — in fact, it shouldn’t. This is your creation. It’s your expression. It should reflect you.

I’m all for this, obviously. But as I wrote last month, social media apps have made it so easy to create a web presence (should I even use that term in 2023?), that buying a domain name, and installing a blogging application, seems like a lot of work.

Still to those willing to put in the hard yards, more power to you. And, for a more… succinct call to action, read Start a Fucking Blog, by Kev Quirk.

RELATED CONTENT

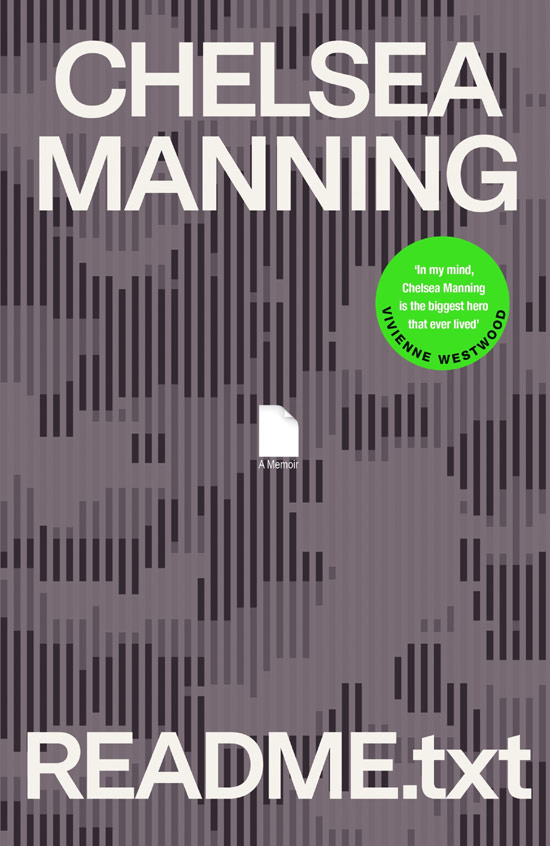

README.txt, Chelsea Manning’s partly redacted memoir

4 January 2023

I’m not sure how often books with parts of their text blacked-out — rendering paragraphs, possibly entire pages, unreadable — are ever published, but README.txt, a memoir by former American solider, turned whistle blower and activist, Chelsea Manning, published by Penguin Books Australia in October 2022, is an example.

In 2010, Manning leaked hundreds of thousands of classified U.S. military documents to WikiLeaks, and a number of media outlets. She was later incarcerated for her actions, but only served several years of a thirty-five year sentence the court imposed on her.

In her book, Manning wrote about releasing the classified documents, and her pre-trial jail time, among other things, but a number of pages have been redacted by the publisher, at least in Australia:

Manning feared being sent to Guantanamo as a terrorist. Her publishers simply feared lawyers: three sections of the book, which would appear to describe documents she uploaded, are blacked out.

It seems only a small portion of the book cannot be read as a result, but I wonder if blacking out pages in books in this way, has any effect on their long term value. In the same way, for instance, mint made errors can sometimes make a coin featuring some sort production flaw, more valuable.

Blacked out text would make Manning’s memoir unique in a certain way, possibly making it collectible for that reason. Time will tell.

RELATED CONTENT

books, Chelsea Manning, writing

Ten word creative summaries: a secret sentence, a North Star to write by

22 December 2022

A journalist once told me he could summarise any article he was writing with a sentence of no more than ten words. These ten words, or less, outlined the purpose of the piece he was working on, whether it be five hundred words, or fifty thousand.

If he found himself floundering, or stuck, while writing, he’d refer back to his article outline so as to refocus on the task at hand. He ventured that the ten word outline could be applied to any creative endeavour, be it a painting, a sculpture, whatever. If the basic objective of the project could not be described in ten words or less, something was wrong, he said.

I think he was onto something. Let’s look at an example. If I had been making the 2019 film Portrait of a Lady on Fire, instead of Céline Sciamma, my ten word or less outline for the project might’ve been: “a painter falls in love with her subject.” If I realised, as the supposed filmmaker, that I was losing sight of the story, while trying to tie the myriad other elements of the narrative into a cohesive whole, I could go back to my outline for guidance.

American author Austin Kleon has a similar methodology, though he titles it with a little more pizzazz. He refers to his ten word outline as a secret sentence, and sees it as his “North Star”. Should Kleon need guidance while working on a writing project, he looks to his secret sentence:

Since we both write books, I confessed that with each book I usually have a secret sentence that I write down somewhere but don’t show to anybody. That sentence is sort of my North Star for the project, the thing I can rely on if I get lost. The sentence usually doesn’t mean anything to anyone other than me. And sometimes it’s pretty dumb. (When I was writing Show Your Work! the sentence was: “What if Brian Eno wrote a content strategy book?”)

A sort of star to steer by while writing. I like the sound of that.

RELATED CONTENT

creativity, psychology, writing

Authors back up your manuscript every day, it’s not difficult

19 December 2022

Image courtesy of malcevsasha.

The story about British writer Ann Cleeves losing her laptop, and, in the process, potentially the manuscript of the novel she was currently writing, is enough to give anyone who’s ever written a book nightmares for weeks. Some people devote years to developing their manuscript. Imagine if it were lost — irretrievably — in the blink of an eye?

While Cleeves was reunited with her laptop, it had been run over by a car, and buried under snow for a day or two, in Lerwick, a town in Scotland’s Shetland archipelago.

Cleeves was unsure whether any data could be retrieved from the device, but was thankful she’d emailed herself a copy of the document shortly before misplacing the laptop. “Not too much will be lost,” said Cleeves. Let’s hope so. Let’s also hope Cleeves has a clear memory of what work had not been copied. Losing even a couple of paragraphs could be devastating, especially if an author’s power of recall is not the best. The best part of the story may be lost forever.

But this sort of thing should not happen anymore. Authors no longer handwrite, or use typewriters, to write book drafts. They no longer depend on keeping a handwritten backup of their work. Nor do they need to use carbon-copying, or photocopying to create duplicates. At least they shouldn’t.

Who can forget the scene from Richard Curtis’ 2003 film Love Actually, when pages of the manuscript Jamie Bennett, portrayed by Colin Firth, is working on, blow into a nearby pond?

Why the hell wasn’t Bennett keeping any copies — whatsoever — of his work? More the point, why the hell was Bennett even using a typewriter? Because he sought to be charmingly technophobic? That’s not endearing, that’s foolhardy. Laptops were hardly uncommon in 2003, and were surely a more sensible option for a writer who seemed to be moving about, as Bennett was.

He’d have easily been able to keep a copy of the work-in-progress on a laptop’s hard drive (HD). And for extra peace of mind, he could have transferred copies to a thumb drive or two. Thumb drives had been around for a couple of years by that stage. But you don’t need me to tell you that.

Of course it could be argued Bennett had other things on his mind at the time we saw him. A recent relationship breakdown. Emerging feelings for the woman, Aurélia, who was looking after his villa in France. Not to mention the part the manuscript blowing into the pond played in the fledgling romance between Jamie and Aurélia. But rom-com movies aside, word processors, and other writing apps, make backing up documents as valuable as a manuscript easy.

No writer should find themselves in the situation either Cleeves or Bennett did. Because there are plenty of simple, secure backup options. Dropbox and OneDrive, for example, are among numerous cloud storage services. If you prefer to keep your work within the four walls of your home, setting up a separate backup folder on your HD isn’t difficult. Regularly copying that backup folder, and its contents, to a couple of thumb drives, which you keep somewhere safe, is an additional safeguard.

And although not the most secure, there’s the aforementioned method of emailing yourself copy of the manuscript file. It’s better than nothing. Preferably that’s a password protected document, and your email account is with a reputable web/cloud based provider.

Leaving a single copy of your manuscript on your computer HD is leaving all your eggs in one basket. Sadly though, I suspect there are plenty of writers who still do not understand this. But failing to back up work isn’t down to a lack of backup options, it’s more down to a lack of routine. For many authors, making copies of their work files may not be a part their work routine. If that’s you, change that conduct today. Make it the last thing you do at the end of each writing day.

Add “backup work files” to your daily to-do list now.

RELATED CONTENT