Waking Romeo (published by Allen & Unwin, March 2021), by Sydney based Australian author Kathryn Barker, has been named winner of the Best Science Fiction Novel, in the 2021 Aurealis Awards.

It’s the end of the world. Literally. Time travel is possible, but only forwards. And only a handful of families choose to remain in the ‘now’, living off the scraps that were left behind. Among these are eighteen-year-old Juliet and the love of her life, Romeo. But things are far from rosy for Jules. Romeo is in a coma and she’s estranged from her friends and family, dealing with the very real fallout of their wild romance. Then a handsome time traveller, Ellis, arrives with an important mission that makes Jules question everything she knows about life and love. Can Jules wake Romeo and rewrite her future?

The Aurealis Awards have been honouring Australian science fiction, fantasy, and horror writers since 1995. The full list of winners in the 2021 awards can be seen here.

Pistol, trailer, a six-part TV series tracking the rise, and fall, of legendary punk band, the Sex Pistols, debuts on Tuesday 31 May 2022.

The series is based on the 2016 memoir Lonely Boy, by Steve Jones, former guitarist of the English group, and is directed by British filmmaker Danny Boyle, he of Trainspotting, Shallow Grave, and Slum Dog Millionaire, fame.

Actually we’re not into music, we’re into chaos.

Hell yeah. Time to break out Never Mind the Bollocks, Here’s the Sex Pistols, the group’s only studio album, released in 1977. God Save the Queen, Anarchy in the UK, Pretty Vacant… the music only gets better as time goes by.

The Hubble constant expresses the rate at which the universe is expanding. The problem is though, no one has been able to nail down a precise value for the constant. That is, until now.

When the Hubble Space Telescope was launched in 1990 the universe’s expansion rate was so uncertain that its age might only be 8 billion years or as great as 20 billion years. After 30 years of meticulous work using the Hubble telescope’s extraordinary observing power, numerous teams of astronomers have narrowed the expansion rate to a precision of just over 1%. This can be used to predict that the universe will double in size in 10 billion years.

That’s mind blowing. To say the least. The already enormous cosmos will one day be twice its present size. Too bad no one here today will be around to see it. But what does it matter anyway? Well, you’d be surprised. Given some two point two million new books are published every year, one can only imagine how many more publications there’ll be in ten billion years’ time.

With a much larger universe by then, it’s comforting to know there will be space to put them somewhere…

Tomb of Sand (published by Penguin Random House India, March 2022) by New Delhi based Indian author Geetanjali Shree, and translated by Daisy Rockwell, has been named winner of the 2022 International Booker Prize.

In northern India, an eighty-year-old woman slips into a deep depression after the death of her husband, and then resurfaces to gain a new lease on life. Her determination to fly in the face of convention – including striking up a friendship with a transgender person – confuses her bohemian daughter, who is used to thinking of herself as the more ‘modern’ of the two. To her family’s consternation, Ma insists on travelling to Pakistan, simultaneously confronting the unresolved trauma of her teenage experiences of Partition, and re-evaluating what it means to be a mother, a daughter, a woman, a feminist.

Frank Wynne, Booker Prize judges chair, described Tomb of Sand, also the first novel originally written in any Indian language, and the first book translated from Hindi, to win the award, thusly:

This is a luminous novel of India and partition, but one whose spellbinding brio and fierce compassion weaves youth and age, male and female, family and nation into a kaleidoscopic whole.

The Dancing With No Music art exhibition opened at aMBUSH Gallery in the Sydney suburb of Waterloo last night. On show was the work of National Art School second year Master of Fine Art students, including Jessica Callen, Emily Ebbs, Joseph Christie Evans, Daniel McClellan, Nina Radonja, Wolfgang Saker, Kansas Smeaton, Jack Thorn, and Elle Wickens.

The diverse works in Dancing With No Music are anchored and inspired by a quote from German philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, “And those who were seen dancing were thought to be insane by those who could not hear the music.” Through their varied painting practices, it explores the concept that in making art, individuals conjure up certain methods, inspired by their own ‘music’. Much like the artists’ varying perspectives, when creating their work the ‘dance’ is to their own music and not a collective rhythm.

The exhibition closes on Sunday 29 May 2022. Check out a few more of my photos from the opening night here.

Melbourne based Australian author, Anna Spargo-Ryan, who’s novels include The Paper House, and The Gulf, writes about the hope and relief some Australians are feeling — at least momentarily — as a result of the change of government in Australia last weekend.

For today – and maybe only for today, but we’ll see how things pan out – I feel held. Not fighting the solipsistic dread with weapons made out of my own wellbeing, but part of a community that has chosen to vote for the betterment of others. That’s new. It feels good to sit with it, to briefly imagine, in the words of famous internet depressed person Allie Brosh, that maybe everything isn’t hopeless bullshit.

The mood is a little different presently, but there often is when a new administration is elected. Whether things will be become “better” long term? That remains to be seen.

The late American concept artist, who died last week at the age of 90, was behind the concept and design of many of the vessels seen in the early Star Wars films.

His staggering number of designs and prototype models essentially formed the visual Star Wars starship lexicon, and include the X-wing, Y-wing (the first approved design, according to The Making of Star Wars), TIE fighter, Star Destroyer, Death Star, landspeeder, sandcrawler, and blockade runner (a design originally intended for the Millennium Falcon).

Entries are open for the 2022 Oodgeroo Noonuccal Indigenous Poetry Prize until Sunday 5 June 2022, from Indigenous writers across Australia, of all ages, for unpublished poetry.

This prize is named in honour of Oodgeroo Noonuccal, the first Aboriginal Australian to publish a book of verse (with permission from the Walker family, and in close consultation with Quandamooka Festival). The Oodgeroo Noonuccal Indigenous Poetry Prize is open to all Indigenous poets, emerging and established, throughout Australia.

C Raina MacIntyre, Professor of Global Biosecurity at UNSW, writes about the recent monkeypox outbreak, which may be linked to the discontinuation of vaccine programs for the now eradicated smallpox virus, an immunisation that also offered protection from monkeypox.

Scientists have puzzled over why a previously rare infection is now becoming more common. The vaccine against smallpox also protects against monkeypox, so in the past, mass vaccination against smallpox protected people from monkeypox too. It is 40 years since smallpox was declared eradicated, and most mass vaccination programs ceased in the 1970s, so few people aged under 50 have been vaccinated. There are even fewer in Australia, where mass smallpox vaccination was never used, and an estimated 10% of Australians have been vaccinated. The vaccine gives immunity for anything from five to 20 years or more, but may wane at a rate of about 1-2% a year.

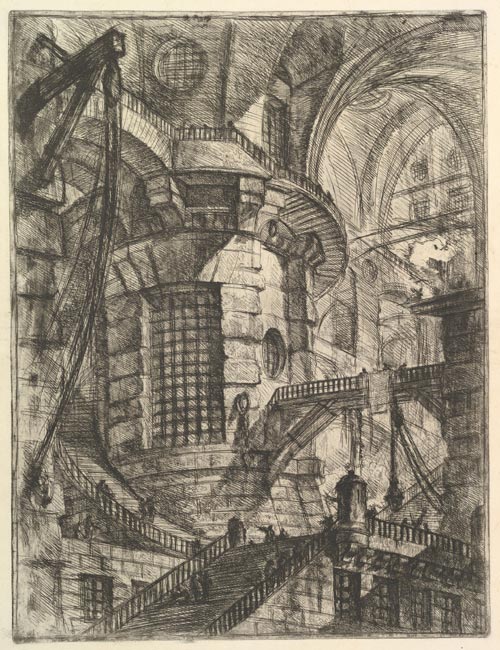

Detail from Imaginary Prisons, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Warning, spoilers follow. Return to this article once you’ve finished reading the book.

Imagine you live in a sprawling multi-storied house. The lower levels are flooded by an ocean, while the upper floors are shrouded in mist and clouds. The seemingly endless labyrinth like hallways are adorned with classical style marble statues, and for whatever reason, sea birds have taken to nesting among some of these figures. But it’s not really a house you’re in, it’s more like a complex with the dimensions of a city, and one none too small at that.

This is the world, Piranesi, the titular character in the second novel of British author Susanna Clarke (published by Bloomsbury Publishing, August 2021), finds himself in. Piranesi knows little about how the house came to be, or when he arrived there, although he has vague recollections of living elsewhere before. Come to that, Piranesi knows hardly anything about himself. He’s perhaps aged in his mid-thirties, and if pressed, couldn’t even be sure his name was Piranesi.

Despite these peculiar circumstances, Piranesi otherwise seems content, and goes about his day to day life as if nothing were amiss. But how would you feel were it you in Piranesi’s place? Wouldn’t you wonder how you ended up in this predicament, and whether there was a way leave, and return to the real world? Wouldn’t you miss family and friends, and wonder if they felt the same way? Wouldn’t you crave the company of others at least some of the time?

But Piranesi doesn’t appear to be the least bit perturbed. Why though? Does he have some sort of problem? Does he loathe all people, and is thankful for the sanctuary the house offers, a place devoid of humans? Or is he perhaps an introvert, who’s found his happy place? Yet Piranesi isn’t completely alone in the house. Once or twice a week, he goes to a certain area of the complex, where he briefly meets a middle-aged man, whom Piranesi refers to as The Other.

If Piranesi knows little about himself, he knows even less about The Other. He has no idea who this gentleman really is — although he believes him to be some sort of academic — nor does he know where The Other resides in the house. The Other meanwhile frequently questions Piranesi, and even sets him tasks, some relatively arduous. One such request required Piranesi to walk to a distant point in the house, on a journey lasting two days return.

To make a comparison, and better understand the scale of the house, I looked up the walking time and distance from Sydney’s CBD to the western suburb of Penrith on Google, and was advised the trek is approximately fifty-six kilometres in length, and the non-stop walk would take almost twelve hours.

Of course the question of exactly what sort of place Piranesi finds himself in came up repeatedly as I read the novel, particularly as he never encountered anyone else — at least not at first — in the sprawling complex. While plenty of Clarke’s readers (myself included) have ideas as to the nature of the house, and what it really is, I found myself wondering how Piranesi could remain oblivious to his acute isolation, and not miss the company of other people.

After all, surely not even the most extreme of introverts would continuously crave the deep solitude of the apparently empty house. But there were indications Piranesi was lonely. He regarded the sea birds nesting in the statues in some of the hallways as friends, and would often have conversations — albeit one-sided — with them. But when it becomes obvious another person is lurking, out of sight, in the house, Piranesi is keen to find out who they are.

In trying to understand Piranesi’s apparently people averse personality, I would describe him as an introvert. But no ordinary — if there is such a thing — introvert. To live alone for years in a vast complex, spending perhaps an hour at most, once a week, with one other person could not be anyone’s ideal. While it can argued something else is going on, that he is unaware of, Piranesi’s outright acceptance of his plight remains compelling. Piranesi is certainly an introvert, but he’s more, he’s an introvert on steroids.