Showing all posts tagged: science fiction

That time Douglas Adams unofficially signed copies of his books in Sydney, Australia

22 July 2024

If you enjoyed the novels of late British author Douglas Adams, you may enjoy this in-depth article about his later life, by Jimmy Maher.

Adams, it seems, did not restrict his particular brand of humour to the written word. A regular customer at a coffee shop I used to go to, told me about an encounter (of a sort) with Adams, in Sydney, Australia, sometime in the late 1990’s. My friend at the coffee shop once worked at a large bookshop in Sydney’s CBD.

He told of the day that Adams — who was presumably in Australia promoting his latest work — arrived at the shop unannounced, and made his way to the sci-fi section. Apparently, his most recent book, plus a selection of others, were on display in a promotional cardboard gondola, similar to what you see on this webpage.

Adams, without saying a word to anyone, pulled a pen from his pocket, and proceeded to sign random copies of his books. Before turning to leave, he scrawled his name across the top of the gondola, and walked out of the shop, again, without saying a word to anyone.

My friend told me how a huddle of bewildered bookshop staff quickly gathered at the gondola, trying to make sense of what had just happened. “Was that him?” was a phrase uttered numerous times apparently. Signed copies of Adams’ novels must have been a windfall for those who bought them…

RELATED CONTENT

authors, books, Douglas Adams, literature, novels, science fiction, writers

Seventy-five of the best sci-fi books, but I only ever read one

16 July 2024

I might be a fan of science-fiction stories, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Trek, Star Wars, and the like, but of the seventy-five titles listed by Esquire magazine, on their best sci-fi books of all time, I’ve only read one. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, by Douglas Adams. That’s it.

1984, by George Orwell? No. Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley? Ditto. Dune, by Frank Herbert. Same. And I’m pretty sure none of these were required reading at school either. The list of non-reads, of course, goes on. I have seen the film adaptations of a few of them though.

Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel, which ranks at number nine on the Esquire list, is definitely a novel I’d like to read, and is on my TBR list. One day I’ll be able to say I’ve read two of them.

RELATED CONTENT

2001: A Space Odyssey, books, novels, science fiction

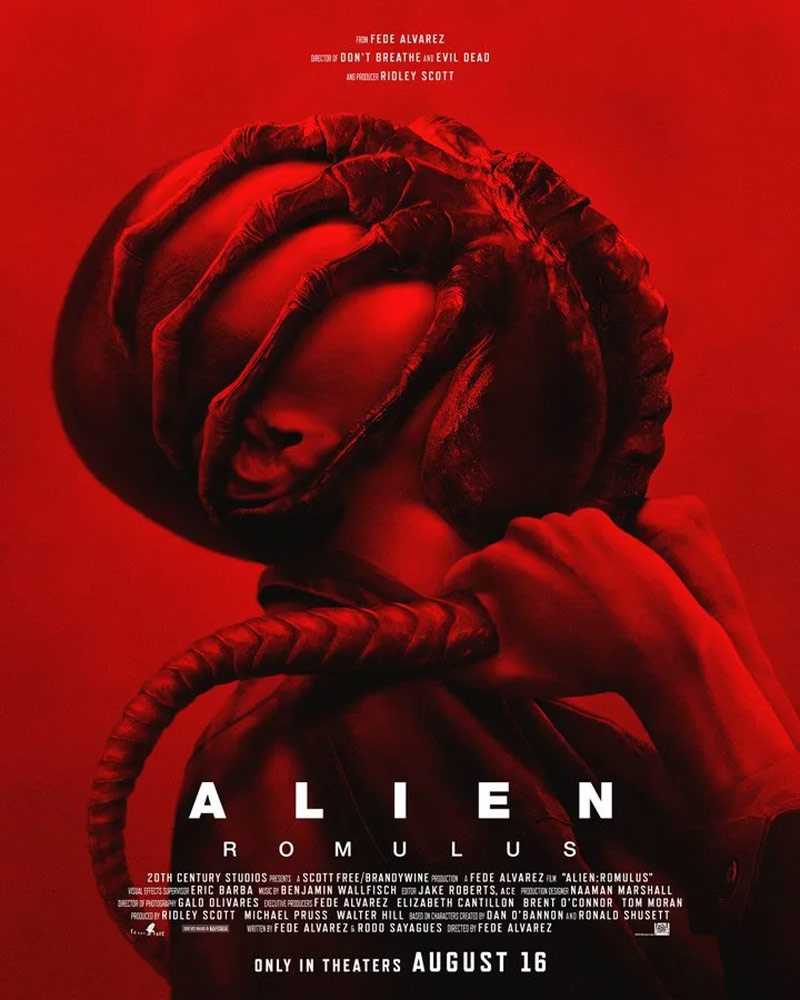

Alien: Romulus, the Alien story continues. Great poster though

7 June 2024

Best I keep this brief, especially after complaining about film franchises continually rebooting and retelling the same story. Alien: Romulus (isn’t Romulus a planet in the Star Trek universe? Yeah, I thought so), is a story about some people on a spaceship, whose lives are threatened by a sinister alien stowaway. Reminds me a lot of a film called Alien, but that must be a coincidence, right?

Anyway, here’s the teaser/trailer for Alien: Romulus.

You’d have thought better lit spaceships would have been designed after Alien, but no. Like, wouldn’t it be a good idea to eliminate as many dark nooks and crannies as possible, so you know, sinister aliens can’t hide in them, and terrorise the crew?

Well-lit spaceships are also kind of practical, sinister aliens notwithstanding. Wouldn’t the crew want to be able to walk around the vessel, without tripping over, because they can’t see where they’re going? But what’s the point of utile design, if it means the same film can’t be remade time and again?

While there’s a stack of films whose trailers were better than the film itself, we just might find the poster for Alien: Romulus trumps both trailer and the feature itself. Alien: Romulus opens in Australian cinemas on Thursday 15 August 2024. Needless to say, I’ll be camping outside the cinema the night before so I can be among the first to see it on opening day.

RELATED CONTENT

films, movie posters, science fiction, trailers

The Acolyte, a new addition to the ever expanding Star Wars universe

28 March 2024

The great thing about the Star Wars universe is the way it can move up down left right forwards and backwards. Like any good fiction franchise, the potential to create new stories, new universes within a universe even, are virtually limitless. This even though I’m way behind on anything Star Wars beyond most of the movies (mainly the Skywalker Saga films) released to date.

But since Disney bought the Star Wars franchise from creator George Lucas, it has been in overdrive expanding exponentially. The Acolyte is the latest offering from this exponentially expanding universe, and is set about one hundred years before events of The Phantom Menace, in what is referred to as the High Republic era.

The trailer looks impressive, and the new show begins streaming on Tuesday 4 June 2024.

RELATED CONTENT

science fiction, Star Wars, trailer, video

Lando Calrissian story now to be told as a film, not a TV series

16 September 2023

The Star Wars origin stories keep a coming. Lando Calrissian, one timer owner of the Millennium Falcon, apparent scoundrel, administrator of Cloud City, and later a general in the Rebel Alliance, is set to feature in his own big screen production.

A Calrissian backstory has been on the cards for some time, but was originally to be the subject of a TV series. Last Thursday however, news broke that series producers, Disney+, had decided to opt for a movie instead. Donald Glover, who portrayed a younger Calrissian in the 2016 Star Wars film Solo: A Star Wars Story, will reprise his role in the proposed feature length origin story, which at this stage appears to be simply titled Lando.

But if producers feel a Calrissian origin story is necessary, let’s hope they get it right. Solo, starring Alden Ehrenreich in the titular role, was underwhelming. To say the least. Han Solo is a character who works best as a happy-go-lucky, fly-by-the-seat-of-his-pants enigma, of a, well, scoundrel, one of whom we knew little about, a point reiterated by Ben Sherlock, writing for Game Rant, in 2021:

Han’s introduction in the shadiest corner booth of Mos Eisley Cantina in the original 1977 Star Wars movie already tells us everything we need to know about the character. He’s an intergalactic pirate and smuggler who’s only interested in money; his best friend (and, seemingly, only acquaintance in the galaxy) is a Wookiee named Chewbacca; and he’s the captain of the Millennium Falcon, the ship that made the Kessel Run in less than twelve parsecs.

There’s a sea of characters in the Star Wars universe, many of whom are more deserving of origin stories. Take Wuher, owner of the infamous Mos Eisley Cantina, where we of course first met Solo. Wuher’s no ordinary guy working a bar though. His is a story that needs exploring, as I’ve said before.

RELATED CONTENT

film, science fiction, Star Wars

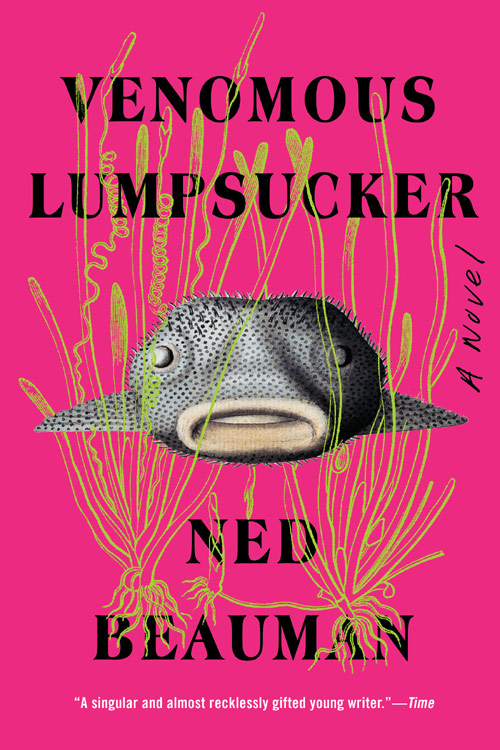

Venomous Lumpsucker wins 2023 Arthur C. Clarke book award

21 August 2023

Book cover of Venomous Lumpsucker, written by Ned Beauman.

British novelist and screenwriter Ned Beauman has been named winner of the 2023 Arthur C. Clarke Award science fiction book of the year, with his fifth novel, Venomous Lumpsucker, which was published by Penguin Random House.

Going by the publisher’s outline, Venomous Lumpsucker has the lot. A cli-fi, sci-fi dystopian chiller-thriller set in the near future, in a world possibly irreparably damaged by climate change:

The near future. Tens of thousands of species are going extinct every year. And a whole industry has sprung up around their extinctions, to help us preserve the remnants, or perhaps just assuage our guilt. For instance, the biobanks: secure archives of DNA samples, from which lost organisms might someday be resurrected . . . But then, one day, it’s all gone. A mysterious cyber-attack hits every biobank simultaneously, wiping out the last traces of the perished species. Now we’re never getting them back.

Karin Resaint and Mark Halyard are concerned with one species in particular: the venomous lumpsucker, a small, ugly bottom-feeder that happens to be the most intelligent fish on the planet. Resaint is an animal cognition scientist consumed with existential grief over what humans have done to nature. Halyard is an exec from the extinction industry, complicit in the mining operation that destroyed the lumpsucker’s last-known habitat.

Across the dystopian landscapes of the 2030s — a nature reserve full of toxic waste; a floating city on the ocean; the hinterlands of a totalitarian state — Resaint and Halyard hunt for a surviving lumpsucker. And the further they go, the deeper they’re drawn into the mystery of the attack on the biobanks. Who was really behind it? And why would anyone do such a thing?

The prize, awarded since 1987, is presented annually to the best science fiction novel first published in the United Kingdom in the previous calendar year, and is named after British author and futurist, Arthur C. Clarke, who died in 2008.

RELATED CONTENT

Arthur C Clarke, climate fiction, literary awards, Ned Beauman, science fiction

Bill Murray had Asteroid City cameo appearance, sort of

3 July 2023

A scene from Bill Murray’s “cameo” in Wes Anderson’s film Asteroid City.

American actor Bill Murray has starred in all but two of Wes Anderson’s feature length films. Murray missed participating in Anderson’s latest, Asteroid City, after being side-lined by a Covid infection. Murray had been cast as a motel manager, but Steve Carell was brought in instead at the last minute.

But that didn’t stop the veteran actor, and Anderson stalwart, from making an appearance on the Asteroid City set, after he had recovered. In a “retro” trailer, posted by the New Yorker, Murray can be seen in a specially created role, walking through the township, where he meets Jason Schwartzman, who in this instance portrays someone called Jones.

RELATED CONTENT

Bill Murray, film, science fiction, Wes Anderson

Optimism powers Star Trek’s enduring popularity says Anson Mount

27 June 2023

Long running science-fiction franchise Star Trek, which first to air in the 1960’s, is still with us today because of its intrinsic sense of optimism. This according to Anson Mount, who portrays Captain Christopher Pike, in the latest variant of the story, Strange New Worlds. For anyone not up with the play, Pike commanded the USS Enterprise prior to Captain Kirk.

Mount is on to something. Dystopian sci-fi is fun to look at for sure, but only for so long.

RELATED CONTENT

Mixed reviews for Asteroid City by Wes Anderson, a film for fans only?

10 June 2023

Still from Asteroid City, directed by Wes Anderson.

Asteroid City, the latest feature by American filmmaker Wes Anderson, premiered in Australia at the Sydney Film Festival on the evening of Thursday 8 June 2023. While there was much excitement in the lead up to the release of Anderson’s eleventh film, reactions so far from viewers and critics who have seen Asteroid City, do not quite match the pre-release hype.

It’s early days though. The film is yet to commence its theatrical run, and to date has mostly been seen only at media preview screenings, and film festivals. It could be argued these viewers, generally made up of film critics and seasoned film-goers, are a little more particular than wider audiences.

Still, some of the early film ranking metrics are not exactly encouraging. Rotten Tomatoes, the go-to gauge of a movie’s likability, presently gives Asteroid City a score of seventy-five percent. Metascore meanwhile, which aggregates the scores movie writers assign to a film through Metacritic, rates Asteroid City at seventy-three out of one-hundred.

The film’s IMDb rating, based on scores by IMDb members, sits at just under seven out of ten. All of these numbers still make Asteroid City worth watching in my opinion.

But bloggers and influencers who have seen early screenings, are distinctly mixed in their appraisals. Swara Salih, writing for But Why Tho?, thought Asteroid City’s biggest problem was none other than Wes Anderson:

What gets in the way of Asteroid City’s success as a narrative was Anderson himself. The writer-director’s insistence on meta commentary results in what could have been one of his most ambitious and groundbreaking films that instead collapses into a narrative mess.

Ali Naderzad, a film writer at Screen Comment, was at odds with Anderson’s trademark saturated pastel pallet, which he suggested worked against the film:

“Asteroid City” is a visual feat of a movie with little in the way of substance, in fact, this might be the most contrived Wes Anderson film I’ve watched. Scarlett Johansson, Tom Hanks, Liev Schreiber and Adrien Brody star in it, which adds heft but the photography is helliciously rendered in saturated pastels and so it’s weird.

Zornitsa Staneva, a staff writer at Tilt Magazine, was critical of Anderson’s penchant for constantly featuring oversize ensemble casts:

Does Wes Anderson invoice based on the number of Hollywood names stuffed in his distended cast? Is Wes Anderson blinded by narcissism to the extent that all he cares about is having a foot long list of cast credits, held tenuously together by a pretentiously self-referential vanity project?

On the flip side, Ben Rolph, writing for AwardsWatch, described Asteroid City as more of the same from Anderson, which was a good thing, albeit a touch more melancholic than usual:

With an explosion of pastel colours, precise camera moves and a whimsical script, Asteroid City is Wes Anderson operating at his best, still doing his usual quirky thing. His latest is another testament to the ongoing power of his one-of-a-kind, special style of filmmaking which here develops to become more mature and melancholic as a family deals with some serious issues.

Finally, Michael Walsh, who was in attendance at the premiere screening at the Sydney Film Festival, was likewise upbeat:

Quirky, offbeat and existential, Asteroid City is yet another darling little feature from the whimsical Wes Anderson that unites a stacked cast, consummate craftwork, and a surprising story that elicits good laughs and deep questions about life, purpose and legacy to deliver one of Anderson’s more character driven and emotionally resonate films in recent memory.

Anderson has an unconventional style of storytelling, which is something to be thankful for. While not all of his titles have one-hundred percent agreed with me, so far there’s not been one I’ve disliked. Asteroid City remains a film I’m hanging out to see.

RELATED CONTENT

film, science fiction, Wes Anderson

Gaia, symbol of climate change failure, in Every Version of You, by Grace Chan

5 June 2023

Image courtesy of Pete Linforth.

Warning: spoilers ahead. Return to this article once you’ve finished reading the novel.

Every Version of You, published by Affirm Press in 2022, is the debut novel of Melbourne based Australian author Grace Chan. Set in the late twenty-first century, primarily in Melbourne, Chan’s novel is about a young couple, Tao-Yi and her boyfriend Navin, and a momentous decision they need to make, which has life changing consequences.

Climate change has rendered Earth almost uninhabitable. Outdoor activities have become uncomfortable and dangerous. People need to don protective clothing and equipment before leaving the cocoon-like sanctuary of their dwellings. Body suits to block the Sun’s burning rays. Goggles and facemasks to combat dust, and other airborne irritants.

But the creation of a would-be new world, a “hyper-immersive, hyper-consumerist virtual reality” named Gaia, offers humanity an alternative to the world outside. And while this digital, artificial, macrocosm, mimics the old world in virtually every way, it also offers inhabitants a whole lot more.

Accessing Gaia, called logging in, is facilitated by climbing into a small, diving bell like chamber, filled with a gel-like liquid, called a neupod. While people’s bodies lie immersed in the pod’s gel, their minds roam free in Gaia, and they go about their lives, as normal. Except here, their presence takes the form of a digital avatar, one they are able to continually customise.

They go to work and school. They see friends and family. They engage in sporting and recreational activities. People “live” in Gaia just as they do in the real, outside, world. But within its realm, people can do more than live their old lives. They can venture to places they once only dreamed of, and become someone they could never have been otherwise.

Gaia, a promise of eternal life, but at a cost

Like everyone else, Tao-Yi and Navin switch back and forth between Gaia and the outside world, although Navin spends more time in Gaia than Tao-Yi. But one day a technology emerges allowing people to permanently meld with Gaia, through a process called “Uploading”.

In essence, Uploading, also known as mind uploading, allows a person to live forever within Gaia’s seemingly boundless domain. But there is a crucial caveat. Once uploaded, a person cannot return to the old world. Not, at least, as a corporeal entity. Uploading transforms a person into a conscious digital entity, through a procedure that extracts their every thought, memory, and personality.

A person’s no longer needed body is disposed of in manner they choose beforehand, once Uploading is completed. Despite Tao-Yi’s misgivings, Navin was a keen proponent. And not just because he saw himself as an early adaptor. Navin was also afflicted with a chronic illness, one that medicine could not alleviate. Uploading would allow Navin to live disease free.

And there were doubtless others in Navin’s position. Medical science could offer these people no hope, but Uploading, and becoming a digital version of themselves, would completely eliminate their ailments. For some, the decision to Upload was easy to make. They could enjoy full “health”, and also be free of the ravages of climate change. To say nothing of “living” forever.

Although in a minority, there were people — called holdouts — who refused to Upload. They wished to remain in the “meatspace”, a derogatory term given to the old world. Xin-Yi, Tao-Yi’s mother, was among them. And even Tao-Yi — for the benefits Uploading bestowed upon Navin — was far from convinced that permanently merging with Gaia was the right thing to do. And for good reason.

Gaia, a symbol of climate change denial

Tao-Yi knew Gaia was not a solution to climate change, only a means by which to escape it. To her, and other holdouts, Gaia was humanity’s way of signalling defeat in the battle to restore Earth’s environment to the way it once was. But not only that. Gaia, while being heralded as a new beginning for humanity, also potentially spelt the end of the line for humans.

Aside from a small number of holdouts braving life in the near inhospitable real world, all of humanity’s eggs were in the single basket that was Gaia. Its digital inhabitants had condemned themselves to eternal imprisonment on Earth. Gaia also left humanity all the more vulnerable to some sort of planet-wide calamity, such as the asteroid impact that brought about the end of the dinosaurs.

It was be hoped the tech savvy denizens of Gaia would eventually figure out a way to leave Earth, and at least put down roots elsewhere in the solar system. If not beyond. But a global catastrophe was not the only danger facing Gaia. The digital realm also depended on an army of (presumably self-replicating) robots to maintain its infrastructure.

There would be the hope the robots continued to serve, and replace themselves. But what if these maintenance droids infused themselves with an intelligence of their own? And what if they one day turned against their digital masters, and pulled the plug on them?

Some of these concerns — and could they be the basis for a sequel, or even an Every Version of You expanded universe? — are alluded to in the novel, even if they are beside the point. Gaia is a potent symbol of climate change denial, and the unwillingness, by some people, to do anything about it. Gaia might promise eternal life, but that could be an eternity spent regretting sacrificing Earth to climate change.

Gaia, why does the name sound familiar?

In Greek mythology Gaia is the goddess of Earth, and the mother of all life. She is one of the “primordial deities”, the first generation of Greek gods, and the grandmother of Zeus, god of sky and thunder, and later king of the cosmos, and the other Greek gods.

As a name for the digital realm humanity withdraws to, Gaia may also derive from the Gaia hypothesis, which was formulated by late British scientist and futurist James Lovelock in the 1970s. His theory proposes “living organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings on Earth to form a synergistic and self-regulating, complex system that helps to maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet.”

In Every Version of You, humanity has well and truly failed to “maintain and perpetuate the conditions for life on the planet.” But by creating a new, artificial, domain named Gaia, perhaps the people of the late twenty-first century — up to their eyes in denial — could claim to have succeeded in achieving this goal.

RELATED CONTENT

books, climate change, climate fiction, Grace Chan, science fiction