Showing all posts tagged: science fiction

36 Streets by T R Napper wins 2022 Aurealis best sci-fi novel

4 June 2023

Book cover of 36 Streets, written by T R Napper.

Australian science fiction writer T. R. Napper was named winner of the Best Science Fiction Novel award, with 36 Streets, in the 2022 Aurealis Awards, at a ceremony in Canberra, last night.

The novel, Napper’s debut, is set in a futuristic version of Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam. In 36 Streets, the city is occupied by China, but residents seem to be preoccupied by a highly addictive stimulation of the American-Vietnamese war of the mid-twentieth century:

Lin ‘The Silent One’ Vu is a gangster in Chinese-occupied Hanoi, living in the steaming, paranoid alleyways of the 36 Streets. Born in Vietnam, raised in Australia, everywhere she is an outsider. Through grit and courage, Lin has carved a place for herself in the Hanoi underworld under the tutelage of Bao Nguyen, who is training her to fight and survive. Because on the streets there are no second chances.

Meanwhile the people of Hanoi are succumbing to Fat Victory, an addictive immersive simulation of the US-Vietnam war. When an Englishman — one of the game’s developers — comes to Hanoi on the trail of his friend’s murderer, Lin is drawn into the grand conspiracies of the neon gods: the mega-corporations backed by powerful regimes that seek to control her city.

Lin must confront the immutable moral calculus of unjust wars. She must choose: family, country, or gang. Blood, truth, or redemption. No choice is easy on the 36 Streets.

Established in 1995, the Aurealis Awards honour works of original speculative fiction written by Australian authors, which are published in the preceding calendar year. A full list of winners in the 2022 awards can be seen here.

RELATED CONTENT

Aurealis Awards, literary awards, science fiction, T. R. Napper

Earth should have the cool Star Trek universal time stardate

17 May 2023

Image courtesy of Michal Jarmoluk.

The popular, long running, Star trek science-fiction franchise, thanks to its creator Gene Roddenberry, has given us a lot. There are fantastic starships — all shapes and sizes — capable of traversing the galaxy in a flash. There’s the USS Enterprise from the original series, and then USS Titan-A, seen in the third series of the recently screened Picard TV series.

There’s the old school favourite crew: Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Uhura, Scotty, Sulu, and Chekov. Then there’s the more recent Discovery crew, whose exploits predate those of the original Enterprise, and then stretch all the way into the thirty-second century, nine hundred years later.

There’s no question about it. Star Trek has the lot. The aliens and the adventure. The amour and the antagonism. The adversity and the aspiration. The lovable and the despicable. Phasers and transporters. And of course, stardate.

Wait up, stardate? What’s that?

Put simply, stardate is a time standard used throughout the Star Trek universe. And a pretty essential one at that. If you find figuring out time differences between certain countries on Earth confusing, imagine trying to do the same across the galaxy. Even doing so within the solar system would be a nightmare. Earth is part of a family of eight (depending who you ask, that is) planets orbiting the Sun. The rotational periods of each body, relative to Earth, with the possible exception of Mars, are just about unique.

So, if it’s four o’clock in the afternoon in London, what is the local time in the vicinity of the Gusev crater on Mars? That might be easy to figure out, assuming Mars one day ends up with formal time zones. But what of other locations around the solar system? For instance, a “day” on Venus lasts 5832 hours. That’s the same as 243 days on Earth. In fact a day on Venus is longer than a year on Venus, which clocks in at about 225 Earth days. Earth based time keeping methods might not then work too well on Venus.

But the time difference question becomes even murkier when the numerous moons of the solar system’s planets are taken into account. Between them, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune have a stack of satellites. And while I’m not aware of any plans to establish bases on these bodies, I’m sure the idea has been broached. If it’s eight o’clock in the morning in Suva, Fiji, what’s local time at a base of ours on Triton, one of Neptune’s satellites? Assuming, that is, bases could be established in the first place, and Triton is assigned time zones in the process.

Well, stardate to the rescue. Establishing a universal, or blanket time, on all places beyond Earth, would make time keeping across the solar system simple. And the galaxy. And, come to that, it’d be pretty good on Earth also. If it’s stardate something or other in London, it will be the same stardate in Wellington, New Zealand. But let’s come back to that thought later.

How is stardate worked out?

Great then. Stardate sounds like some sort of universal time system. Whether you’re on the east coast of Australia, or one of the moons of Sherbet III (which I’m sure is out there somewhere) thousands of light years distant, stardate remains the same. No need to adjust for differences in time zones. Or even time dilation, a phenomenon which appears to be absent from the Star Trek universe. But stardate is a deceptively complicated time tracking construct, and that, ironically, is a product of Star Trek, rather than stardate.

In early episodes of what’s called The Original Series (TOS) of Star Trek, which screened in the 1960’s, stardate made for a useful way of concealing the actual calendar year setting of the show. Perhaps Star Trek producers wanted to protect themselves from cynical segments of the audience (What? Some Star Trek viewers were cynics?), who might berate them for making the wrong calls about the timings of the invention of certain technologies seen in the show.

No one could castigate the producers for offering the wrong date for the advent of warp drive, since no one could (at the time) correlate a given stardate to a specific year. As the show went on though, it became apparent the early Star Trek stories played out in the twenty-third century, or about two hundred years in the future. Still, while stardate was effective at hiding the calendar year, screenwriters were reportedly casual in the application of stardate, at least initially, using, it seems, whatever number came into their heads.

This would have frustrated fans who were intrigued by stardate, and were trying to figure out how it was calculated. In early TOS episodes, stardate was a four figure number, with a decimal point, for instance, 1502.1. The decimal value represented a segment of a twenty-four hour Earth day, which was divided by ten. On my example stardate value of 1502.1, the point one (.1) would be a time between midnight and 2:40AM. Starships however still used twenty-four hour clocks, for (local) ship time, and these are visible in some Star Trek stories.

Why is stardate (needlessly) complicated?

This is because each new Star Trek “spin-off” series, or generation, seem to use stardate differently.

While stardates in TOS shows and movies didn’t move past four figures, that changed when The Next Generation (TNG) arrived in 1987. Here stardates had advanced to values of over forty thousand. The stardate of the first episode of the first TV series of TNG was about 41000. This number advanced by one thousand with each successive series of TNG. The stardate at the beginning of the second TNG series would have been about 42000. Then 43000 for the third series, and so on.

This system suggested an Earth calendar year equated to one thousand stardate units. But only for TNG stories. TOS stardates were another matter. Between the first TOS TV show, broadcast in the 1960’s, with James Kirk as captain of the USS Enterprise, to the last appearance of Kirk and the TOS core crew in 1991, thirty-three years (in canon) is said to have elapsed. Yet the stardate in The Undiscovered Country, the final story with the TOS crew, was stated as 9529.1. Surely it should have been over 33000 by then?

How confusing is that? We’re also told the TNG stories commenced ninety-five years after the last TOS story, but I think this figure refers to the final TOS TV show, and not the subsequent movies the TOS crew were in. The Motion Picture, the first of the TOS movies, although made ten years after the final TOS TV show, is set five years after events of the TV show, where the stardate is given as 7410.2. The stardate for the final TOS TV show, broadcast in 1696, is 5943.7.

The difference in the two suggests stardate advances by about three-hundred units per year for the TOS stories. If the first TNG TV show is set about seventy years after The Undiscovered Country, the final TOS story, surely the TNG stardate should be closer to eighty-thousand, instead of about forty-thousand, if stardate advances in thousand units increments every year. But trying to figure out stardate conventions is almost as confusing as trying work out the differences between the world’s various time zones.

Yet if the time span in calendar years between The Motion Picture (stardate 7410.2) and The Undiscovered Country (stardate 9529.1) is about twenty years, that gives stardate an annual value of about one-hundred and five units. My head is spinning. But if stardate — for all the difficulty in figuring out how it is calculated — was intended as a universal time, it no doubt would have suited the space-faring members of Star Trek’s galactic federation.

If stardate was indeed a universal time, its value would be fixed. It would be the same regardless of an observer’s location in the galaxy, or federation space. And this would obviously have made organising rendezvous, gatherings, and the like, straightforward. Having said that, I suspect stardate operated in tandem with local times on planetary systems across the galaxy, so federation denizens would be accustomed to living with at least two time keeping systems.

Stardate, a universal time for Earth?

If stardate works as a universal time standard around the solar system and beyond, could something similar be adopted on Earth? Doing so would certainly make life a lot easier. A standard, fixed, global time, would eliminate the confusion associated with the current twenty-four separate time zones. In 2014, Matthew Yglesias, co-founder of media outlet Vox, suggested the world consider moving to a single, or “giant” time zone, describing the present time zones as “more trouble than they are worth.”

They were a good idea at the time, but in the modern world they cause more trouble than they are worth. Now that several generations of humanity are accustomed to abstracting time away from the happenstance of where the sun is located, it’s time to do away with this barbarous relic of the past. Everyone on the planet should operate according to a single time — Greenwich Mean Time would be suggested by tradition — and then local schedules could differ from place to place according to personal taste and local practicality.

As I’ve already said, who doesn’t find differences between time zones confusing? And as for daylight saving… well, let’s not go there.

But what if there were a global time, meaning the time was the same everywhere? Would that not make things so much easier? Sure, implementing such a time zone, which perhaps I could refer to here as Earth Time, means plenty would change. But that doesn’t mean doing away with the existing time standards. A global time zone would still be used side-by-side with, say, the existing Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), or Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) time standards, meaning everyone retains the local time they’re used to.

Because if those in the Star Trek universe can live comfortably with two time standards — stardate, and a local time — so can we.

An Earth Time wouldn’t mean moving the whole planet onto the same schedule either. For example, people on the east coast of Australia wouldn’t be waking up in the middle of the night so they could be in sync with sunrise in, say, California. They’d still be rising at their usual time, which would most likely be during daylight hours (assuming they’re not early birds, shift workers, and the like), and living their lives exactly as they always have.

But a global Earth Time would make interacting with people in other parts of the world less bothersome. For example, scheduling a conference call with colleagues in other countries would entail settling on an Earth Time that suited everyone. “Yes, 1530 Earth Time, works for me.” As Yglesias also points out, Earth Time would suit travellers crossing state or national borders. Straight off the bat, they would know exactly how long they would be in transit, without having to work out the differences across various time zones.

If an international flight is scheduled to depart from somewhere at 1100 Earth Time, and reach its destination at 1800 Earth Time, a traveller can immediately see that the flight time will be seven hours. Tell me now, how good is a global time zone?

What format would a global time take?

While an Earth Time would work in same way as stardate, in that it is a universal-like time standard, it would not have stardate’s “count-up” format. Earth Time wouldn’t start at zero, which presumably (maybe) stardate did at one point, and continue going up infinitely, rather it would be based on the far simpler twenty-four hour clock. It would start at 0000 each day, and conclude at 2359. An Earth Time could of course have a six-digit format to take seconds into account, allowing for greater precision, for example, 093515.

Expressing Earth Time without the colons seen on most digital clocks could possibly help differentiate Earth Time from local time. Digital clocks could be designed to feature both times. If Earth Time was 065515, local time might be, depending on your location, 15:55:15. Doubtless savvy designers will be able to incorporate both time formats onto analogue (analog) clocks as well. And with potentially two time zones in play, World, and local, a convention governing days would need to be established.

This would probably mean days fall according to World Time. People in some locations may find the day of the week ticking over to the next day at times other than midnight. Someone might, say, be in a meeting at 14:00 local time on Tuesday, but find they have, say, a dentist appointment only an hour later at 15:00, but the day will suddenly be Wednesday. This is because World Time has ticked over to 000000 in the interim. No doubt though our electronic timekeepers and clocks will guide us through these peculiarities.

Making time for global time

Introducing a global time zone would be a huge undertaking, and pose its share of challenges. The process would need to be spread over years, possibly decades, to give everyone a chance to adapt to it, and make the necessary infrastructure changes. But the benefits are well worth considering. If a global time zone doesn’t come to pass though, fret not. Star Trek canon tells us stardate will arrive in around 2266. That’s only about two-hundred and forty years away.

RELATED CONTENT

film, science fiction, Star Trek, television

Every Version of You by Grace Chan optioned for film

13 May 2023

Melbourne based Australian author Grace Chan’s debut novel Every Version of You, has been optioned for film. Cognito Entertainment, a new Los Angeles based film production company, whose goal is to bring weird science to life through story, will oversee the book to screen adaptation:

Neuroscientist and Stanford professor Dr. David Eagleman has teamed up with producers Matt Tauber and Adam Fratto to launch Cognito Entertainment, an independent production company centered around science programming and films. The Los Angeles and Palo Alto-based company has already begun working on scripted television series, documentaries and literary adaptation.

I’m part way through reading Every Version of You as I write this, and I can’t say I’m surprised. While great news for Chan, this is also a positive development for Australian writers of science fiction and speculative fiction, who often struggle to find someone to publish their work.

RELATED CONTENT

Australian literature, film, Grace Chan, science fiction

Daisy Ridley to return in one of three new Star Wars films

8 April 2023

Lucasfilm president Kathleen Kennedy announced three new Star Wars movies at Star Wars Celebration, currently taking place in London. One of the titles will see Daisy Ridley reprise the role of Rey, who featured prominently in episodes seven to nine, in a story that picks up fifteen years after events of The Rise of Skywalker:

The third film to be announced, a project to be directed by Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, has been known about for some time, but appears to have been dogged by changes of direction and staff departures. Obaid-Chinoy’s film will take place 15 years after The Rise of Skywalker and feature Daisy Ridley returning in the role of Rey; it will “tell the story of rebuilding the New Jedi Order and the powers that rise to tear it down”.

Sounds a little like post Return of the Jedi storylines that were plotted out in the Star Wars Expanded Universe (EU) back in the day. Now known as Star Wars Legends, the EU were imaginings of events in the Star Wars stories before, around, and more notably, after episode six.

Most of the main players in the original trilogy (episodes four to six) were part of these post Return of the Jedi EU stories. But episodes seven through nine saw many of them off, so obviously they will be absent. But who knows, maybe not. The Star Wars universe is full of ghosts. Let’s see what happens. And just maybe these new movies will be a little more engaging than the previous three. But again, let’s see what happens.

RELATED CONTENT

Daisy Ridley, film, science fiction, Star Wars

Asteroid City, a film by Wes Anderson

2 April 2023

After an asteroid buzzed uncomfortably close to Earth several days ago, the trailer for American filmmaker Wes Anderson’s new film, Asteroid City, landed, if you’ll excuse the pun. Does this mean Anderson is psychic, or does he have a knack for — if you’ll excuse another pun — hitting the mark? One thing’s certain though, Anderson has a knack for getting it right with cinema-goers, and Asteroid City, billed as science fiction romantic comedy drama, his eleventh feature, looks to be no exception.

What’s Asteroid City about then?

A widower (Jason Schwartzman) is driving his son Woodrow (Jake Ryan), and three daughters, across the United States to see their grandfather (Tom Hanks), during the summer of 1955. Their car breaks down in a town called Asteroid City, situated in the middle of the Arizona desert. They happen to arrive in time for a stargazers’ convention, held on Asteroid Day, which commemorates the day the Arid Plains Meteorite is said to have struck the area, on 23 September 3007 BCE.

Woodrow is intrigued by the event that draws people from across the world, and wants to stay for it. With their car undergoing repairs, Woodrow’s father calls his grandfather, who reluctantly agrees to come and collect his sisters. The widower and his children are not the only visitors to Asteroid City though. Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson), a movie star is also in town. But then strange things begin happening. Loud bangs are heard, and earthquakes rock the town.

Locals begin reporting the presence of extra-terrestrials, and the authorities decide to seal off Asteroid City, until they can figure out what’s going on. Woodrow and his family, along with the other visitors in town, are forced to stay put. It may not be all bad for the reserved, awkward Woodrow though. He’s met a girl, also in town for the stargazers’ convention, and the two seem to feel they share a connection…

For those who in late, Wes Anderson is…

A filmmaker who hails from Houston, Texas. Although Anderson wanted to be a writer, he was always making films. Growing up, Anderson often made homemade films, with his siblings and friends. He also worked as a cinema projectionist while at university. He made his first full length feature Bottle Rocket in 1996, which was based on an earlier short film he’d made with the same name. Three of his works feature on the BBC’s 100 Greatest Films of the 21st Century.

There are many ways to describe Anderson’s films. Quirky. Eccentric. Whimsical. Vintage. Nostalgic. With an abundance of rich pastel colours, his stories hark back to a world where life was a little simpler, though a dark streak is often ever present. Stylistically, Asteroid City looks to be no different, but if the trailer is anything to go by, Anderson has ramped up the colour saturation, imbuing the story with a truly fairy tale like quality.

As such Asteroid City is par for the Anderson course, and is his first foray into science fiction, with the possible exception of 2018’s Isle of Dogs.

A sci-fi potpourri perhaps?

While the trailer only offers a glimpse of what’s to come, the references to Steven Spielberg’s 1977 film Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, by Stanley Kubrick, are pretty clear. And after all, how could any Wes Anderson movie with an outer space tack not have a nod to 2001? It remains to be seen whether there are any Star Wars and Star Trek imprints though, but I have a feeling they’ll be in there somewhere.

The gang’s all here

On top of his distinct film and storytelling style, Anderson usually works with the same writers and actors. He often co-writes screenplays with Jason Schwartzman, who stars in Asteroid City, along with frequently collaborating with Noah Baumbach and Roman Coppola. On screen, regular Anderson standbys include Willem Dafoe, Tilda Swinton, Jeff Goldblum, Adrien Brody, Edward Norton, Liev Schreiber, and the aforementioned Scarlett Johansson.

But the large cast features more than just Anderson regulars. Hong Chau, Margot Robbie, Bryan Cranston, Jarvis Cocker, and Sonia Gascón, are also among this ensemble cast of astronomical proportions. Conspicuous by absence though is Bill Murray, who has featured in every Anderson feature except Bottle Rocket. Murray was unable to participate after being diagnosed with Covid, shortly before production commenced. Steve Carell was cast to take Murray’s place instead.

Asteroid City meanwhile is the first Wes Anderson film that Tom Hanks has appeared in.

That’s a wrap, almost…

Despite being set in the Arizona desert, Asteroid City was mostly filmed in Spain, in Chinchón, a town about fifty kilometres to the south east of Madrid. From what I can tell, the Arizona desert sure looks like the Arizona desert, though I’m not sure why Anderson didn’t go for the real thing. Maybe Covid restrictions applying at the time ruled out other locations. Or it could be a matter of convenience, as Anderson lives not too far away in Paris.

I’m also wondering if there’s any significance to the date of Asteroid Day, being 23 September. What’s up with 23 September? It’s probably a totally random date, but I checked for notable past events occurring on 23 September anyway. Encyclopædia Britannica reports American musician John Coltrane was born on that day in 1926, while actor, choreographer, and film director John Fosse died on 23 September, in 1987.

Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud, who devised psychoanalysis, also died that day, in 1939. Perhaps the momentousness of Asteroid Day’s date, if there is one, will come to light at a later time.

Asteroid City is set to premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2023, and open in Australian cinemas on Thursday 22 June 2023.

RELATED CONTENT

film, science fiction, trailer, video, Wes Anderson

Every Version of You, speculative fiction by Grace Chan

5 March 2023

Finding someone to publish science fiction in Australia is difficult but not wholly impossible. A number of Australian authors report difficulty in having works of anything other than contemporary or literary fiction published locally, forcing them to take their work to overseas publishers.

Under these circumstances it would seem Melbourne based Australian author Grace Chan was fortunate. Her debut novel Every Version of You, published by Affirm Press in July 2022, is categorised as speculative fiction after all. Speculative fiction may not be another name for science fiction per se, but speculative fiction is often considered an umbrella term for a number of non-realist fiction genres, including horror, fantasy, and sci-fi.

Every Version of You is set in the late twenty-first century in a world where inhabitants spend most of their time within what is described as a hyper-immersive, hyper-consumerist virtual reality called Gaia. They live almost every aspect of their lives in this digital realm without ever leaving the house. But wait a minute, doesn’t that describe the way many of us already live? Are we not so immersed by the domain on the screen in the palm of our hands that we don’t even blink sideways at the person standing next to us?

Social media gave rise to socialising online, while the COVID-19 lockdowns of recent years made working from home the norm, deepening our engagement with the virtual dimension.

Gaia then sounds very much like an actual place, rather than the product of a speculative fiction writer’s mind. Might these details have somehow escaped the publisher of Every Version of You, who believed the book to be a work of a genre other than speculative fiction? This is surely a hopeful sign for writers of speculative and science fiction in Australia, as their work often explores contemporary, and relevant matters, through a lens other than that of contemporary or literary fiction.

The prospect of uploading one’s consciousness, in a digital format, to the internet, sometimes called mind uploading, is by no means a fanciful notion either. And in the world Tao-Yi, and her boyfriend Navin inhabit, this is something they find themselves grappling with. Tao-Yi, who has reservations about the Gaia concept in any case, is anything but enthusiastic when a technology that allows people to permanently upload their consciousness completely to Gaia, emerges. Navin, in contrast, is all for the idea.

Tao-Yi is confronted with a choice. Follow her boyfriend into this perpetual digital realm, or, like her mother, remain in the real world, but one ravaged by climate change and poverty. Those who reside in the world Chan has created seem to be damned if they do, damned if they don’t.

Chan, who also works a psychiatrist, is a prolific writer of short fiction, with a keen interest in neuroscience, consciousness, empathy, ethics, and the mind-body relationship. One of her short works, He Leaps for the Stars, He Leaps for the Stars, was shortlisted in the Aurealis Awards, a literary prize celebrating the work of Australian speculative fiction writers.

Every Version of You meanwhile has been longlisted for the 2023 Stella Prize. Recognition of a work of speculative fiction by a literary award as highly regarded as the Stellar is certainly positive for writers of the genre in Australia.

RELATED CONTENT

Australian literature, fiction, Grace Chan, novels, science fiction

Melissa Clark-Reynolds and Beth Barany discuss science fiction

27 February 2023

Melissa Clark-Reynolds and Beth Barany talk about writing science fiction on the Writer’s Fun Zone podcast. One point that emerges is science fiction’s relevance to contemporary matters on planet Earth. This at a time when some Australian publishers have no interest in looking at science fiction and fantasy manuscripts, possibly because they deem it irrelevant.

I’ve seen so many different stories use science fiction to explore where we are today. And, there’s something always very surprising about them. I just really enjoy them.

A great point. A lot of sci-fi pertains to the here and now. It’s not all a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far, away. Literary agents and publishers take note.

RELATED CONTENT

Why are Australian publishers averse to science fiction books?

20 February 2023

Australian author Alice Boer-Endacott, writing for the Australian Young Adult Literature Alliance (#LoveOzYA) blog:

However, despite the growing mainstream appreciation of fantasy (and science fiction) texts, especially within YA, Will [Kostakis] notes, “it’s as if we’re conditioned to see something as less worthy just because it is unabashedly fun. The implications of this? We talk less about fantasy books’ craft, we omit some of our finest YA writers from awards conversations, they’re not studied in schools … That last bit is very important in the Australian landscape, where sales are (unfortunately) quite small.” This final point was echoed by an industry insider with whom I had a passing conversation on this subject (they declined to be named). They told me, “the success of YA texts are dependent on whether or not schools pick up class sets, and they are much less inclined to do that with fantasy.”

Some Australian publishers explicitly state they will not accept science fiction and fantasy manuscripts. Some Australian authors meanwhile have reported local agents and publishers will only accept literary fiction manuscripts, and nothing else. Scoring any publishing deal is difficult, but the odds are especially stacked against sci-fi and fantasy writers in Australia.

RELATED CONTENT

books, literature, novels, science fiction

What if 2001: A Space Odyssey was directed by George Lucas?

4 February 2023

Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 sci-fi classic 2001: A Space Odyssey is remixed with George Lucas’ 1977 space opera Star Wars, by YouTuber Poakwoods, and this is the result.

Truly awesome.

Also, it seems hard to believe from the third decade of the twenty-first century that less than ten years separate 2001: A Space Odyssey and the first Star Wars film.

RELATED CONTENT

2001: A Space Odyssey, film, humour, science fiction, video

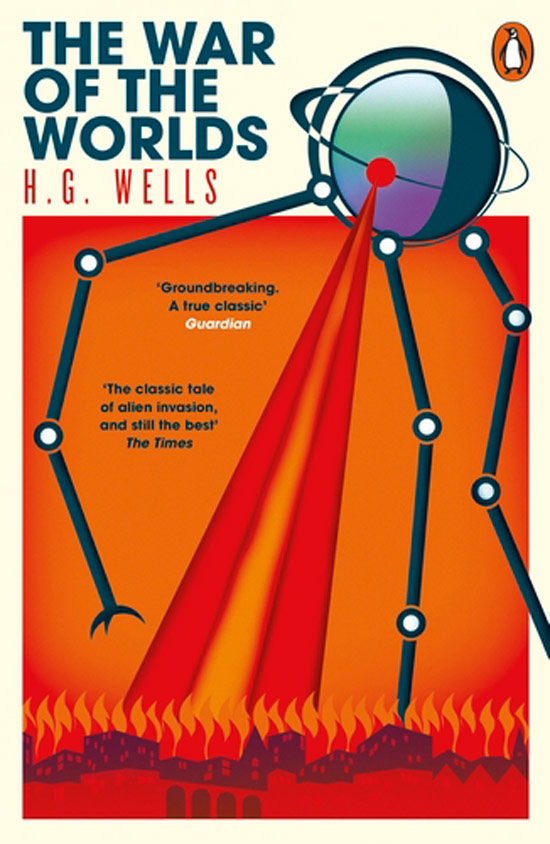

The War of the Worlds, invasion literature by H G Wells with an Australian connection

27 January 2023

When people think of The War of the Worlds, the novel written by late British author H. G. Wells, and published by William Heinemann in 1898, after being serialised in 1897, they think of science fiction.

Yet the story of the inhabitants of Mars crossing the interplanetary void to invade Earth — incidentally one of the earliest examples of alien invasion in English literature — isn’t only sci-fi and/or fantasy, The War of the Worlds is also an instance of invasion literature. Also known as invasion novels, invasion literature was common from the later decades of the nineteenth century — following the publication of The Battle of Dorking, written by George Tomkyns Chesney in 1871 — through until the First World War.

Despite being set in England though, Wells drew inspiration for The War of the Worlds from another hemisphere all together, Tasmania, Australia:

Wells later noted that an inspiration for the plot was the catastrophic effect of European colonisation on the Aboriginal Tasmanians; some historians have argued that Wells wrote the book in part to encourage his readership to question the morality of imperialism.

Invasion literature played a part in influencing public opinion in Britain, and other then imperialistic European nations, through their unsettling premises. Stories such as The War of the Worlds, depicting a ruthless invasion of England by a technologically superior enemy, hopefully helped bring home the horrors of colonisation that were being inflicted upon other cultures.

RELATED CONTENT